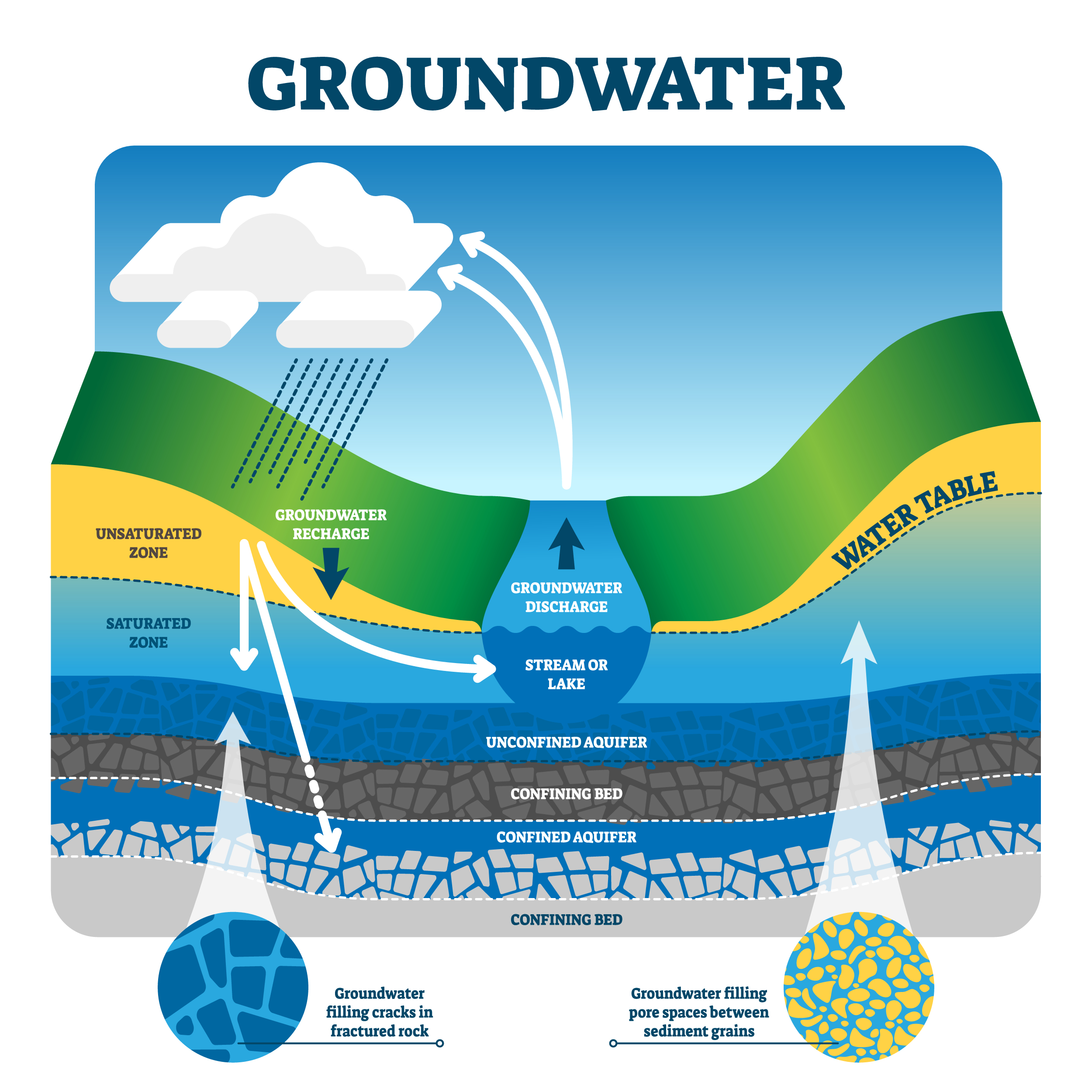

Along with surface water from lakes, rivers, and streams, groundwater that accumulates in underground aquifers is a major source of water for California’s communities and farms, and for the environment. In California, some local groundwater levels are critically declining. Groundwater provides 40 percent of California’s water supply in normal years, and up to 60 percent during dry years. In some California communities, groundwater is the only source of tap water for household use.

In the midst of the severe 2012-2016 drought, the California legislature passed the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) to address the rapid decline of groundwater levels that was occurring mainly in agricultural areas. SGMA requires local water agencies, cities and counties in areas with significant groundwater depletion to form groundwater sustainability agencies (GSAs) and to develop groundwater sustainability plans (GSPs) to achieve groundwater sustainability over a twenty year planning horizon.

A GSP must contain a water budget ensuring that ultimately, the amount of water leaving an aquifer is balanced by the amount of water recharged. GSPs must monitor and manage groundwater levels, groundwater quality, land subsidence, surface and groundwater interconnections, and saltwater intrusion in coastal areas. GSAs are required to consider the interests of all local groundwater users as they develop and implement their plans.

Critically overdrafted groundwater basins, most in the San Joaquin Valley and Central California coastal areas, completed their GSPs in 2020. Other high and medium priority basins have until 2022 to complete their plans. Some groundwater basins, mostly in Southern California, are adjudicated and are not required to develop GSPs. Basin prioritization and adjudicated areas are shown on this map.

Together with water conservation, recharging groundwater aquifers is essential for achieving groundwater sustainability. In wet years Flood Managed Aquifer Recharge (Flood-MAR) can deliver multiple benefits for communities, agriculture, and the environment, especially in the Central Valley. This includes flood risk reduction, ecosystem enhancement, climate change adaption, and working landscape preservation.

Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR) projects in some areas have used multiple means to recharge aquifers, including deep injection methods and the use of urban stormwater and treated wastewater to recharge aquifers.

Groundwater can migrate underground, even between subbasins, in ways we do not understand well. It can be pumped out of the ground and moved to other locations through California’s extensive system of canals. Also, people with rights to both surface and groundwater in one basin can forgo surface water so that it can be moved to another basin while drawing down their own groundwater, impacting other users in their basin. For all these reasons, groundwater management in California will ultimately involve regional as well as local management strategies in order to ensure statewide sustainability.

Diane B. Merrill, Member LWVC Water Committee