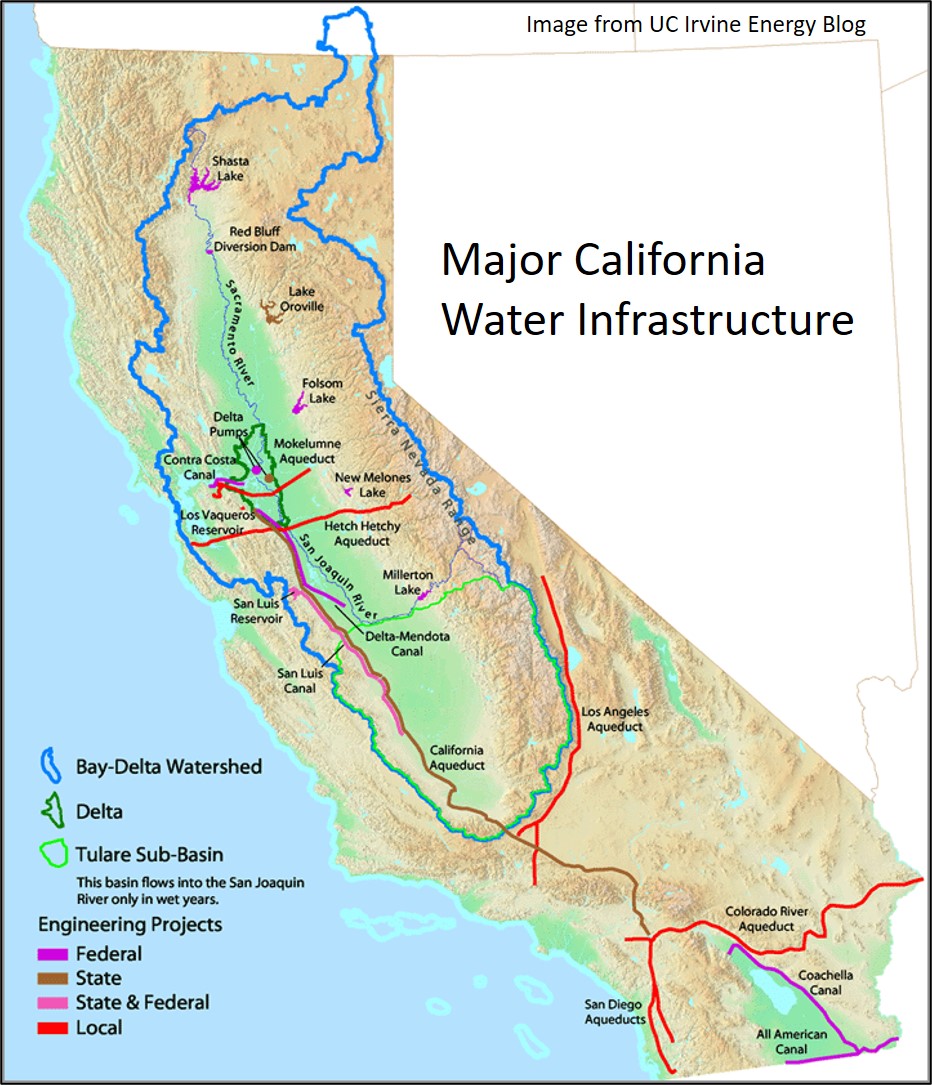

During the 20th century, water project developers relied on engineered infrastructure to serve Californians’ economic aspirations and lifestyle choices in a region that doesn’t have regular rainfall. Principal examples:

- The Los Angeles Aqueduct moves water to Southern California from the eastern side of the Sierras, originally for agriculture and later for urban development..

- The Colorado River Aqueduct and the All American Canal serve urban Southern California and agriculture in the Imperial and Coachella valleys.

- The federal Central Valley Project (CVP) system of dams, reservoirs and canals serves mostly Central Valley agriculture, but also the Central Coast and urban users in Contra Costa and Santa Clara counties.

- The Hetch Hetchy Project, originating in Yosemite, delivers Tuolumne River water across the San Joaquin Valley to the greater San Francisco Bay Area.

- The Mokelumne Aqueduct delivers water to urban users in the East Bay Area.

- The State Water Project (SWP) system of dams, reservoirs, and canals moves water originally identified as “surplus” in the north to meet varied demands occurring in coastal areas, the San Joaquin Valley, and Southern California.

The last four of these projects impact the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta and the San Francisco Bay-Delta Estuary. In 2008, the State Water Resources Control Board reported that the water rights they managed in the Bay/Delta Watershed exceed mean annual natural flow: for every acre foot of water in the Delta Watershed, 8.4 acre feet of water have been promised on paper.

Ongoing water battles between regions, and between urban and agricultural users, reflect “paper water” or other unrealistic expectations that actual supplies cannot reliably meet. When supplies have fallen short of expectations, the Water Board has been pressured to deliver water anyway, even at the expense of endangered species and the health of the people and ecosystem of the Delta and Estuary. When there is no surface water to deliver, users have turned to groundwater, overdrafting it to compensate.

Each of the major water projects faces supply, environmental, and climate challenges that planners did not anticipate. It is no longer clear that more infrastructure is the answer.

Jane Wagner-Tyack, Co-chair, LWVC Water Committee

Coming up next: The Water-Energy Nexus – Moving, heating, and treating water and treating wastewater all together represent one of California’s largest end uses of electricity and of natural gas.